- Home

- Tharoor, Shashi

The Great Indian Novel Page 2

The Great Indian Novel Read online

Page 2

She was in the woods oft the river bank when Shantanu came across her. He was struck first by the unique fragrance that wafted from her, a Brahmin- taught concoction of wood herbs and attars that had superseded the fishy emanations of pre-Parashar days and he was smitten as my father had been. Kings have fewer social inhibitions than Brahmins, and Shantanu did not hesitate to walk into the head fisherman’s hut and demand his daughter’s hand in marriage.

‘Certainly, Your Majesty, it would be an honour,’ my maternal grandfather replied, ‘but I am afraid I must pose one condition. Tell me you agree and I will be happy to give you my daughter.’

‘I don’t make promises in advance,’ the Maharaja replied, somewhat put out. ‘What exactly do you want?’

The fisherman’s tone stiffened. ‘I may not be able to find my Satyavati a better husband than you, but at least there would be no doubt that her children would inherit whatever her husband had to offer. Can you promise her the same, Your Majesty - that her son, and no one else, will be your heir?’

Of course, Shantanu, with the illustrious Ganga Datta sitting in his capital, could do nothing of the kind, and he returned to his palace a despondent man. Either because he couldn’t conceal his emotions or (more probably) because he didn’t want to, it became evident to everyone in or around the royal court that the Maharaja was quite colossally lovesick. He shunned company, snubbed the bewhiskered British Resident on two separate occasions, and once failed to show up at his morning darshan. It was all getting to be too much for the young Crown Prince, who finally decided to get the full story out of his father.

‘Love? Don’t be silly, lad,’ Shantanu responded to his son’s typically direct query. ‘I’ll tell you what the matter is. I’m worried about the future. You’re my only son. Don’t get me wrong, you mean more to me than a hundred sons, but the fact remains that you’re the only one. What if something should happen to you? Of course we take all due precautions, but you know what an uncertain business life is these days. I mean, it’s not even as if one has to be struck by lightning or something. The damned Resident has already run over three people in that infernal new wheeled contraption of his. Now, I’m not saying that that could happen to you, but one never knows, does one? I certainly hope you’ll live long and add several branches to the family tree, but you know, they used to say when I was a child that having one son was like having no son. Something happens and sut! the British swoop in and take over your kingdom claiming the lack of a legitimate heir. They still haven’t stopped muttering about the way I brought you in from, as they think, nowhere. So what happens if you pick a fight with someone, or get shot hunting with some incompetent visiting Angrez? The end of a long line, that’s what. Do you understand why I’m so preoccupied these days?’

‘Yes, I see,’ replied Ganga Datta, who was certain he wasn’t seeing enough. ‘It’s posterity you’re worried about.’

‘Naturally,’ said Shantanu. ‘You don’t think I’d worry about myself, do you?’

Of course that was precisely what Ganga Datta did think, and probably what the ageing Maharaja had hoped he’d think, for the Crown Prince was not one to let matters drop. Kings, he well knew, did not travel to forests alone; there were drivers and aides to witness the most solitary of royal recreations. So a few inquiries about the Maharaja’s recent excursion rapidly led the young man to the truth, and to the hut of the head fisherman.

Ganga Datta didn’t travel alone either. In later years he would be accompanied by a non-violent army of satyagrahis, so that the third-class train carriages he always insisted on travelling in were filled with the elegantly sacrificing élite of his followers, rather than the sweat-stained poor, but on this occasion it was a band of ministers and courtiers he took with him to see Satyavati’s father. Ganga D. would always have a penchant for making his most dramatic gestures before a sizeable audience. One day he was even to die in front of a crowd.

‘So that’s what you want,’ he said to the fisherman, ‘that’s all? Well, you listen to me. I hereby vow, in terms that no one before me has ever equalled and no one after me will ever match, that if you let your daughter marry my father, her son shall succeed as king.’

‘Look, it’s all very well for you to say so,’ said the fisherman uneasily, warily eyeing the ceremonial weaponry the semicircle of visitors was carrying. ‘I’m sure you mean every word you say and that you’ll do everything to keep your vow, but it’s not really much of a promise, is it? I mean, you may renounce the throne and all that, but your children may have, other ideas, surely. And you can’t oblige them to honour your vow.’ His guests bristled, so he added hastily, ‘Forgive me, huzoor, I don’t mean to cause any offence. It’s just that I’m a father too, and you know what children can be like.’

‘I don’t, actually,’ Ganga Datta replied mildly. ‘But I have made a vow, and I’ll ensure it’s fulfilled. I’ve just renounced my claim to the throne. Now, in front of all these nobles of the realm, I swear never to have children. I shall not marry, I shall desist from women, so your daughter’s offspring need never fear a challenge from mine.’ He looked around him in satisfaction at the horror-struck faces of those present. ‘I know what you’re thinking - you’re wondering how I can hope to get to Heaven without producing sons on this earth. Well, you needn’t worry. That’s one renunciation I don’t intend to make. I intend to get to Heaven all right - without any sons to lift me there.’

The head fisherman could scarcely believe how the discussion had gone. ‘Satyavati,’ he called out in joy. ‘The king can have her,’ he added superfluously. ‘And I shall be grandfather to a maharaja,’ he was heard mumbling under his breath.

The wind soughed in the trees, signalling the approach of the monsoon rains, rustling the garments of the consternated courtiers. A stray gust showered petals on to Ganga Datta’s proud head. He shook them off. ‘We’d better be going,’ he announced.

One of the courtiers stooped to pick up the fallen flowers. ‘It’s an omen,’ he said. ‘The heavens admire your courage, Ganga Datta! From now on you should be known as Bhishma, the One Who has Taken a Terrible Vow.’

‘Ganga is much easier to pronounce,’ the ex-Crown Prince said. ‘And I’m sure you know much more about omens than I do; but I think this one means we shall get very wet if we don’t start our return journey immediately.’

Back at the palace, where the news had preceded him, Ganga was greeted with relief and admiration by his father and king. ‘That was a fine thing to do, my son,’ Shantanu said, unable to conceal his pleasure. ‘A far, far better thing than I could ever have done. I don’t know about this celibacy stuff, but I’m sure it’ll do you a lot of good in the long run. I’ll tell you something, my son: I’ve simply no doubt at all that it’ll give you longevity. You will not die unless and until you really want to die.’

‘Thanks awfully, father,’ said Ganga Datta. ‘But right now I think we’d better start trying to get this arrangement past the Resident-Sahib.’

4

‘Wholly unsuitable,’ the British Resident said, when he heard of Satyavati. ‘A fisherman’s daughter for a maharaja’s wife! It would bring the entire British Empire into disrepute.’

‘Not really, sir, just the Indian part of it,’ replied Ganga Datta calmly. ‘And I cannot help wondering if the alternatives might not be worse.’

‘Alternatives? Worse? Don’t be absurd, young man. You’re the alternative, and I don’t see what’s wrong with you, except for some missing details in your . . . ahem . . . past.’

‘Then perhaps I should start filling in some of those missing details,’ Ganga replied, lowering his voice.

There is no record of the resulting conversation, but courtiers at the door swore they heard the words ‘South Africa’, ‘defiance of British laws’, ‘arrest’, ‘jail’ and ‘expulsion’ rising in startled sibilance at various times. At the end of the discussion, Ganga Datta stood disinherited as crown prince, and Shantanu’s strange alliance with Satyava

ti received the official approval of His (till lately Her) Majesty’s Government.

That was not, of course, the end of the strange game of consequences set in train by the wooded wanderings of my malodorous mother. The name ‘G. Datta’ was struck off imperial invitation lists, and a shiny soup-and-fish was shortly placed on a nationalist bonfire. One day Ganga Datta would abandon his robes for a loincloth, and acquire fame, quite simply, as ‘Gangaji’.

But that is another story, eh, Ganapathi? And one we shall come to in due course. Never fear, you can dip your twitching nose into that slice of our history too. But let us tidy up some genealogy first.

5

Satyavati gave Shantanu what he wanted - a good time and two more sons. With our national taste for names of staggering simplicity, they were called Chitrangada and Vichitravirya, but my dismayed readers need not set about learning these by heart because my two better-born brothers do not figure largely in the story that follows. Chitrangada was clever and courageous but had all too brief a stint on his father’s throne before succumbing to the ills of this world. The younger Vichitravirya succeeded him, with Gangaji as his regent and my now-widowed mother offering advice from behind the brocade curtain.

When the time came for Vichitravirya to be married, Gangaji, with the enthusiasm of the abstinent, decided to arrange the banns with not one but three ladies of rank, the daughters of a distant princeling. The sisters were known to be sufficiently well-endowed, in every sense of the term, for their father to be able to stay in his palace and entertain aspirants for their hands. None the less, it came as a surprise when Ganga announced his intention of visiting the Raja on his half-brother’s behalf.

He had been immersing himself increasingly in the great works of the past and the present, reading the vedas and Tolstoy with equal involvement, studying the immutable laws of Manu and the eccentric philosophy of Ruskin, and yet contriving to attend, as he had to, to the affairs of state. His manner had grown increasingly other-worldly while his conversational obligations remained entirely mundane, and he would often startle his audiences with pronouncements which led them to wonder in which century he was living at any given moment. But one subject about which there was no dispute was his celibacy, which he was widely acknowledged to have maintained. His increasing absorbtion with religious philosophy and his continuing sexual forbearance led a local wit to compose a briefly popular ditty:

‘Old Gangaji too

is a good Hindu

for to violate a cow

would negate his vow.’

So Ganga’s unexpected interest in the marital fortunes of his ward stimulated some curiosity, and his decision to embark on a trigamous mission of bride-procurement aroused intense speculation at court. Hindus were not wedded to monogamy in those days, indeed that barbarism would come only after Independence, so the idea of nuptial variety was not in itself outrageous; but when Gangaji, with his balding pate and oval glasses, entered the hall where the Raja had arranged to receive eligible suitors for each of his daughters and indicated he had come for all three, there was some unpleasant ribaldry.

‘So much for Bhishma, the terrible-vowed,’ said a loud voice, to a chorus of mocking laughter. ‘It turns out to have been a really terrible vow, after all.’

‘Perhaps someone slipped a copy of the Kama Sutra into a volume of the vedas,’ suggested another, amidst general tittering.

‘O Gangaji, have you come for bedding well or wedding bell?’ demanded an anonymous English-educated humorist in the crowd.

Ganga, who had approached the girls’ father, blinked, hitched his dhoti up his thinning legs and spoke in a voice that was meant to carry as much to the derisive blue-blooded throng as to the Raja.

‘We are a land of traditions,’ he declared, ‘traditions with which even the British have not dared to tamper. In our heritage there are many ways in which a girl can be given away. Our ancient texts tell us that a daughter may be presented, finely adorned and laden with dowry, to an invited guest; or exchanged for an appropriate number of cows; or allowed to choose her own mate in a swayamvara ceremony. In practice, there are people who use money, those who demand clothes, or houses or land; men who seek the girl’s preference, others who drag or drug her into compliance, yet others who seek the approbation of her parents. In olden times girls were given to Brahmins as gifts, to assist them in the performance of their rites and rituals. But in all our sacred books the greatest praise attaches to the marriage of a girl seized by force from a royal assembly. I lay claim to this praise. I am taking these girls with me whether you like it or not. Just try and stop me.’

He looked from the Raja to the throng through his thin-rimmed glasses, and the famous gaze that would one day disarm the British, disarmed them - literally, for the girls emerged from behind the lattice-work screens, where they had been examining the contenders unseen, and trooped silently behind him, as if hypnotized. The protests of the assembled princes choked back in their throats; hands raised in anger dropped uselessly to their sides; and the royal doorkeepers moved soundlessly aside for the strange procession to pass.

It seemed a deceptively simple victory for Ganga, and indeed it marked the beginning of his reputation for triumph without violence. But it did not pass entirely smoothly. One man, the Raja Salva of Saubal, a Cambridge blue at fencing and among the more modern of this feudal aristocracy, somehow found the power to give chase. As Ganga’s stately Rolls receded into the distance, Salva charged out of the palace, bellowing for his car, and was soon at the wheel of an angrily revved up customized Hispano-Suiza.

If Ganga saw his pursuer, it seemed to make little difference, for his immense car rolled comfortably on, undisturbed by any sudden acceleration. Salva’s modern charger, the Saubal crest emblazoned proudly on the sleek panel of its doors, roared after its quarry, quickly narrowing the distance.

Before long they drew abreast on the country road. ‘Stop!’ screamed Salva. ‘Stop, you damned kidnapper, you!’ Sharply twisting his steering-wheel, he forced the other vehicle to brake sharply. As the cars shuddered to a halt Salva flung open his door to leap out.

Then it all happened very suddenly. No one heard anything above the screeching of tyres, but Ganga’s hand appeared briefly through a half-open window and Salva staggered back, his Hispano-Suiza collapsing beneath him as the air whooshed out of its tyres. The Rolls drove quietly off, engine purring complacently as the Raja of Saubal shook an impotent fist at its retreating end.

‘So tiresome, these hotheads,’ was all Ganga said, as he sank back in his seat and wiped his brow.

6

Vichitravirya took one look at the women his regent had brought back for him and slobbered his gratitude over his half-brother. But one day, when all the arrangements had been made in consultation with his - my - mother Satyavati, the invitations printed and a date chosen that accorded with the preferences of the astrologers and (just as important) of the British Resident, the eldest of the three girls, Amba, entered Ganga’s study and closed the door.

‘What do you think you are doing, girl?’ the saintly Regent asked, snapping shut a treatise on the importance of enemas in attaining spiritual purity. (‘The way to a man’s soul is through his bowels,’ he would later intone to the mystification of all who heard him.) ‘Don’t you know that I have taken a vow to abjure women? And that besides, you are pledged to another man?’

‘I haven’t come . . . for that,’ Amba said in some confusion. (Ever since his vow Ganga had developed something of an obsession with his celibacy, even if he was the only one who feared it to be constantly under threat.) ‘But about the other thing.’

‘What other thing?’ asked Ganga in some alarm, his wide reading and complete inexperience combining vividly in his imagination.

‘About being promised to another man,’ Amba said, retreating towards the door.

‘Ah,’ said Gangaji, reassured. ‘Well, have no fear, my dear, you can come closer and confide all your anxieties to your uncle Gang

a. What seems to be the problem?’

The little princess twisted one hand nervously in the other, looking at her bangled wrists rather than at the kindly elder across the room. ‘I . . . I had already given myself, in my heart, to Raja Salva, and he was going to marry me. We had even told Daddy, and he was going to . . . to . . . announce it on that day, when . . . when . . .’ She stopped, in confusion and distress.

‘So that’s why he followed us,’ said the other-worldly sage with dawning comprehension. ‘Well, you must stop worrying, my dear. Go back to your room and pack. You shall go to your Raja on the next train.’

For Gangaji’s sake I wish that were the end of this particular story, but it isn’t. And don’t look at me like that, young Ganapathi. I know this is a digression - but my life, indeed this world, is nothing more than a series of digressions. So you can cut out the disapproving looks and take this down. That’s what you’re here for. Right, now, where were we? That’s right, in a special royal compartment on the rail track to Saubal, with the lovely Amba heading back to her lover on the next train, as Ganga had promised.

If Gangaji had thought that all that was required now was to reprint the wedding invitations with one less name on the cast of characters, he was sadly mistaken. For when Amba arrived at Saubal she found that her Romeo had stepped off the balcony.

‘That decrepit eccentric has beaten, humiliated, disgraced me in public. He carried you away as I lay sprawling on the wreck of my car. You’ve spent God knows how many nights in his damned palace. And now you expect me to forget all that and take you back as my wife?’ Salva’s Cambridge-stiffened upper lip trembled as he turned away from her. ‘I’m having your carriage put back on the return train. Go to Ganga and do what he wishes. We’re through.’

And so, a tear-stained face gazed out through the bars of the small-windowed carriage at the light cast by the full moon on the barren countryside, as the train trundled imperviously back to Ganga’s capital of Hastinapur.

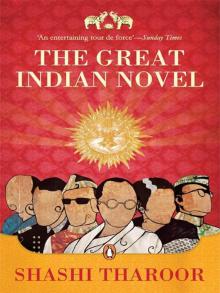

The Great Indian Novel

The Great Indian Novel